A recent report released on October 16 by the Ukrainian Foreign Intelligence Service (HUR) has drawn global attention to an emerging geopolitical fault line: China and North Korea’s expanding footprint in Russia’s Far East. The report warns that Beijing and Pyongyang are gradually transforming parts of this sparsely populated but resource-rich region into zones dominated by foreign economic interests and labour control—challenging Russia’s long-term sovereignty over nearly half of its territory.

HUR asserts that China is executing a strategy of “creeping demographic expansion” across Russia’s Far East—from Vladivostok to the Ural Mountains. Nearly two million Chinese nationals now live and work in the region, compared to just 609,863 Russians, according to World Population Review data. Many Chinese workers reside there visa-free and enjoy easy access through special economic zones established by Moscow to invite investment. North Korea, too, has a foothold. Around 15,000 North Korean labourers are officially stationed in the region, an arrangement that also brings Pyongyang valuable foreign currency.

These figures are not merely demographic trivia; they may be harbingers of long-term strategic realignment. Kyiv’s intelligence agency warns that Russia could eventually lose control over 40 percent of its own territory, as the Far East evolves from a Russian periphery into a theatre of Chinese and North Korean economic influence—and potentially political leverage.

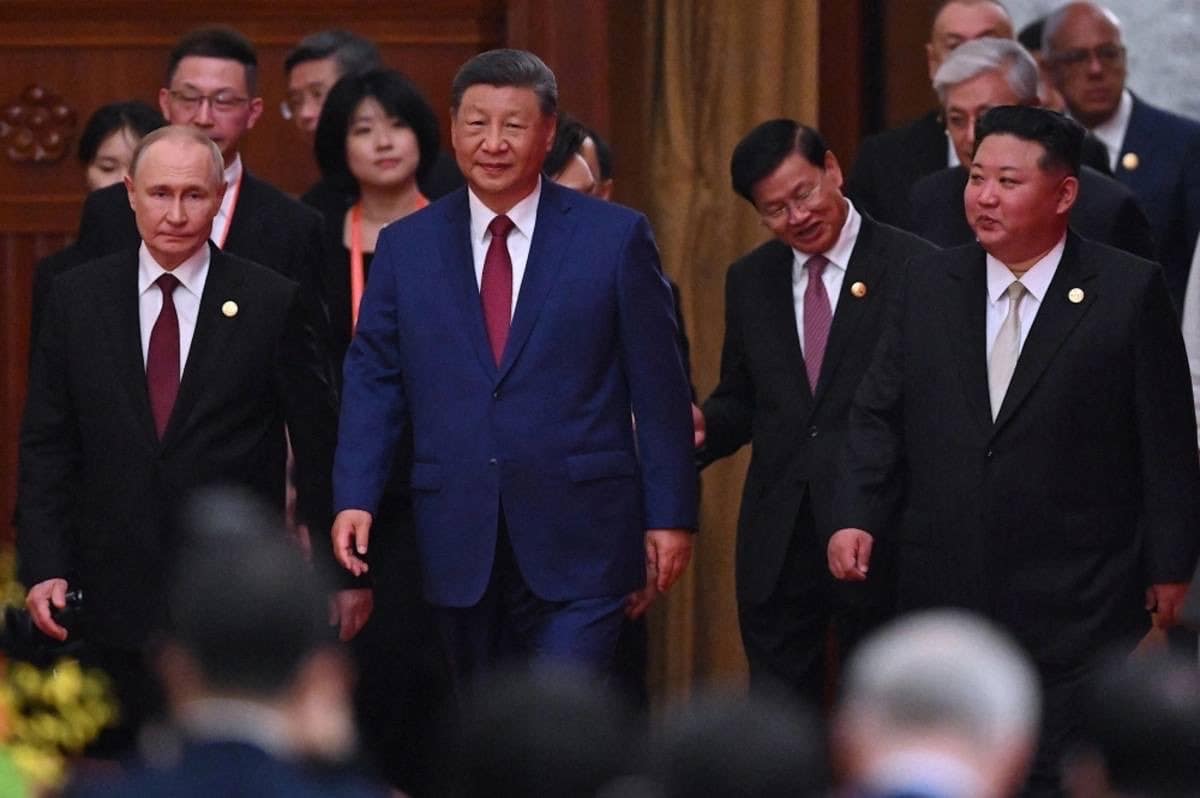

Yet Moscow appears untroubled. It, to a large extent, reflects a calculated balancing strategy by Moscow. Facing Western sanctions and battlefield setbacks in Ukraine, Russia has been pushed into a tighter embrace with Beijing and Pyongyang. Reports—even though denied by the Kremlin—suggest the presence of Chinese and North Korean personnel supporting Russian military efforts in Ukraine. Whether or not these claims are true, the alignment is real.

Russia and China officially proclaim a “no-limits” partnership, but this relationship is built on strategic convenience, not trust. Moscow is acutely aware of its growing asymmetry with Beijing. China has become Russia’s economic lifeline, largest energy customer, and main technological backdoor. But it is also a rising power with a long memory. For many in China, Vladivostok—known historically as Hǎishēnwǎi—is seen as “lost territory” ceded to Tsarist Russia under the 1860 Treaty of Peking. Chinese officials are careful to avoid revanchist rhetoric, but nationalist voices have increasingly revived historical narratives reminding audiences that the Russian Far East once belonged to China. Today, the Chinese border lies 45 kilometres from Vladivostok, and the demographic trend is unmistakable.

It is in this context that Russia’s warming ties with North Korea acquire new meaning. Moscow’s pivot to Pyongyang is not simply a wartime convenience but also can be a balancing act against Chinese overreach. Earlier this year, Russia and North Korea signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, expanding cooperation beyond military supplies into trade, technology, and potential joint infrastructure development. Some reports suggest this growing partnership has unsettled China, which has long treated North Korea as its own sphere of influence.

This evolving triangle is rewriting Northeast Asian geopolitics. China, Russia, and North Korea present a united anti-West front, yet mutual suspicion runs deep. Beijing champions cautious pragmatism to preserve its global ambitions. Moscow, increasingly isolated, acts with fewer constraints. Pyongyang sees opportunity—its partnership with Russia lifts it from isolation and gives it a second great-power sponsor besides China.

Fault Lines in the Far East

The HUR report raises strategic questions for Moscow that might be uncomfortable for the country. The war in Ukraine provides a template for modern territorial revisionism, one that China may study carefully. If demographic trends in the Far East continue, Beijing could one day argue—using Russia’s own justification in Ukraine—that it must “protect ethnic Chinese communities abroad.” All it would take is distributing Chinese passports to residents in border areas—something Russia itself did in Donbas to justify intervention. For the time being, Moscow’s growing relationship with North Korea might be a deterrence against Chinese presence in the Far East region. Pyongyang’s presence introduces another volatile variable. Pyongyang does not honour international rules or borders, and if empowered by its military partnership with Russia, it could become both a deterrent against China and a destabilizing proxy in the region.

Conclusion

Russia believes it is strengthening its geopolitical hand by aligning with Beijing and Pyongyang. In reality, it may be eroding its own territorial integrity. The Far East is quietly becoming a zone of overlapping interests, hidden rivalries, and future contestation. Moscow thinks it is balancing China with North Korea but it may instead be inviting a silent struggle for control over its most vulnerable frontier. The alliances Russia sees as its wartime assets could, over time, become the reasons for its future territorial dilemmas. The Far East is no longer just a distant frontier; it is Russia’s next geopolitical fault line.

*Dr. Indrani Talukdar is a Fellow at the Chintan Research Foundation, New Delhi.